The 5,000 square-metre (53,820 square-foot) high-altitude wind power capture kite was unfurled at a test site at Alxa Left Banner in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region on Wednesday, according to state broadcaster CCTV.

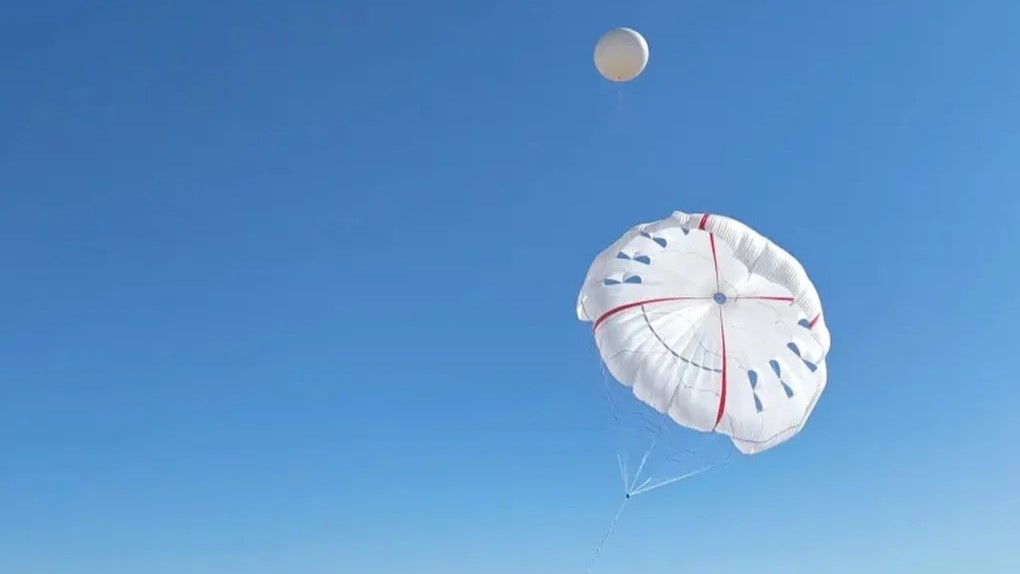

Resembling a parachute, the power-generating kite was developed by the China Energy Engineering Corporation as part of the country’s first national research and development project for high-altitude wind power.

Tethered to a generator on the ground, the kite can fly at an altitude exceeding 300 metres (984 feet).

During the tests, the 5,000 square-metre kite – about the size of 11 standard NBA basketball courts – as well as two connected 1,200 square-metre kites were lifted into the air by helium balloons and successfully deployed and retracted.

Cao Lun, chief commander of the national high-altitude wind project, told state news agency Xinhua on Wednesday that the experiment measured the tension of the kite “in natural wind conditions when it is open and then calculated its opening characteristics”.

Cao said the tests of both types of kites would provide important data for the design and optimisation of a ladder-like wind energy system.

The wind power kites could be deployed at heights exceeding 5,000 metres and cut land use by 95 per cent as well as reduce steel consumption by 90 per cent compared with traditional onshore wind projects, according to CCTV.

They could also lower the cost of electricity per kilowatt-hour by 30 per cent, with one 10-megawatt high-altitude wind power system enough to power more than 10,000 households per year, the state broadcaster said.

High-altitude wind has emerged as a promising renewable energy source, offering enormous generation potential because of the much higher wind speeds and energy density compared with surface wind resources.

The wind energy contained within high altitudes alone could theoretically meet existing global energy demand by a factor of more than 100, according to studies from 2009 and 2012 led by researchers with the Washington-based Carnegie Institution for Science.

Airborne wind energy systems rely on aircraft to harvest wind at high altitudes hundreds or thousands of metres above the Earth’s surface.

These systems can be split into two categories: one in which the electricity generator itself is airborne and another in which the flying parts of the system are used to drive an electricity-generating system on the ground, according to the United Nations.

The cost of the airborne energy harvesting units could be kept low because they are often made of lightweight materials and require minimal use of steel and concrete.

Similar kite systems are being developed elsewhere in the world, including by the Dutch start-up Kitepower, whose kites are flown in continuous cycles of figure-eight patterns to produce energy at the ground station to which they are tethered.

China is also working on developing airborne turbines, with the world’s largest airborne wind turbine, about the size of a basketball court and the height of a 13-storey building, lifting off in September.

The airship-like S1500 became the first turbine of its kind to generate one megawatt of power during a test flight in China’s western Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

The turbine floats on helium-filled shells and delivers electricity back down to the ground using heavy-duty cables.