The push for renewable energy has led scientists to explore sources once thought of as useless. From food waste to plant fibers, researchers are looking at nature’s discarded materials in search of sustainable power.

The challenge is to find solutions that are not only green, but also simple and inexpensive enough to work in real-world conditions.

One team in Canada believes it has found such a solution in something most people toss in the trash: walnut shells.

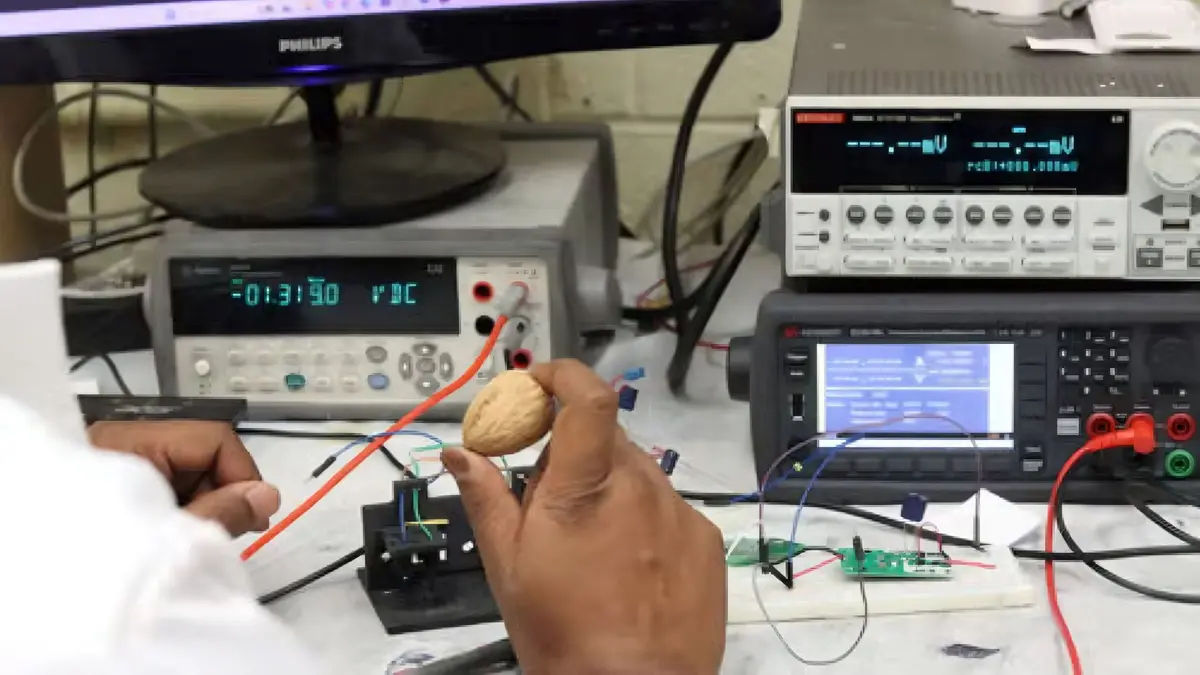

Researchers at the University of Waterloo have developed a device that can turn this agricultural waste into clean electricity, powered only by water droplets.

The coin-sized invention, called a water-induced electric generator (WEG), is able to generate enough energy to run small devices such as calculators.

While modest in scale today, the technology hints at a new way to create power for electronics in areas where batteries or wired electricity are impractical.

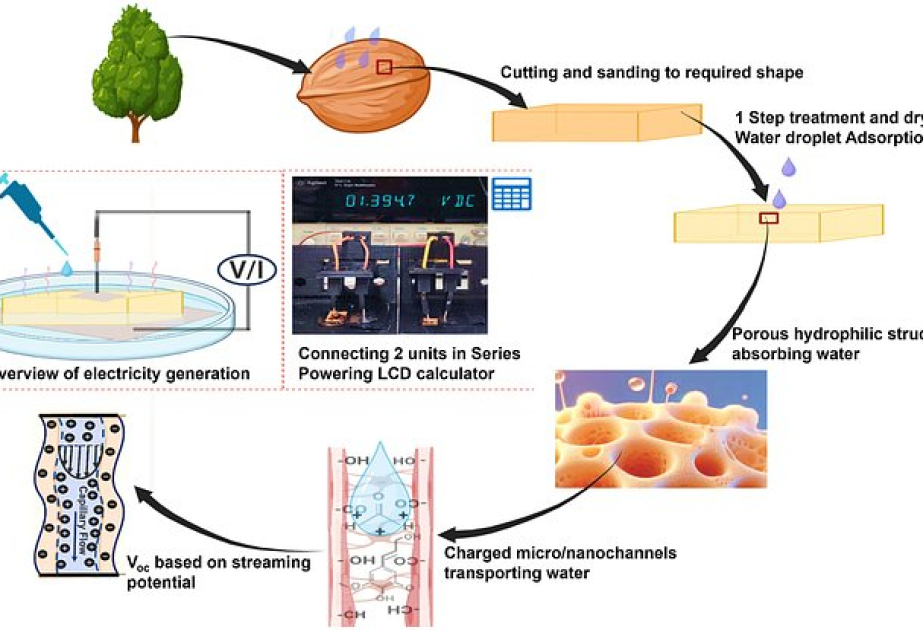

The WEG taps into a field known as hydrovoltaic energy harvesting. When water evaporates from a surface, it carries along electrically charged ions.

The movement of these ions across the porous structure of a walnut shell sets up an electrical imbalance, which in turn generates electricity.

“It all happens with nothing more than a single droplet of water and the shell’s natural architecture, no crushing, soaking or complex processing needed,” said Nazmul Hossain, a Waterloo PhD student in mechanical and mechatronics engineering. “It’s a simple, yet powerful example of turning waste into clean energy using nature’s own power.”

Hossain first became intrigued after eating a hazelnut and placing its shell under an electron microscope.

The intricate pattern he saw, part of the nut’s natural system to move water and nutrients, struck him as perfectly suited for harvesting energy.

The Waterloo team tested four different kinds of nut shells. Walnuts proved the most effective for energy production. To improve performance, the shells were cleaned, treated, polished, and cut into precise shapes.

Each unit of the WEG contains the processed walnut shell, water droplets, electrodes, wires, and a 3D-printed case.

Connecting four of these units produced enough energy to run an LCD calculator, proving the practicality of the design.

“This technology could be a game-changer for powering small electronic devices, especially in remote or off-grid areas,” Hossain said. “Imagine environmental sensors monitoring forests, IoT and wearable health devices, disaster-relief equipment – all running on tiny water droplets from the air.”

The next step for the research is to make the device wearable. The team is experimenting with designs that can harvest energy from sweat during exercise or from raindrops in outdoor environments.

They are also investigating practical uses such as water-leak sensors in buildings.

The group has tested wood as an alternative material, but walnut shells continue to show the strongest results.

Hossain’s work has been carried out under the guidance of Dr. Norman Zhou, professor of mechanical and mechatronics engineering, and Dr. Aiping Yu, professor of chemical engineering.

The study is published in the journal Energy & Environmental Materials.